Hedge Accounting Under IFRS 9: Rebalancing – What Is This New Concept?

Hedge accounting belongs to the most difficult accounting areas and I published a few articles on this topic on IFRSbox – for example, here and here.

Today, I’m delighted to present another hedging article written by Mr. Kevin Mitchel,Partner – Advisory Services at Rochford, the leading treasury advisory house in Australia advising on in excess of AU$20 billion in financial market risk.

Kevin clarifies a totally new concept of rebalancing. I added my example in the end. Enjoy!

Key terms

IFRS 9 introduces a new concept called ‘Rebalancing’ that did not form part of IAS 39. The purpose of this technical update is to delve a little deeper into what rebalancing means, with some practical examples included.

Let’s start with a re-cap of some key terms to be used in this article:

- Hedged item – an asset or liability with underlying exposure to market risks

- Hedging instrument – the financial instrument used to hedge the exposure risk (hedged item) with offsetting movements in either fair value or cash flows

- Hedge ratio – the ratio between the amount of hedge item and the amount of hedging instrument in terms of their relative weighting (in a one-to-one relationship expressed as 1:1)

- Basis risk – basis risk is the chance that the basis will have strengthened or weakened from the time the hedge is implemented to the time when the hedge is removed

What is ‘rebalancing’ and why is it done?

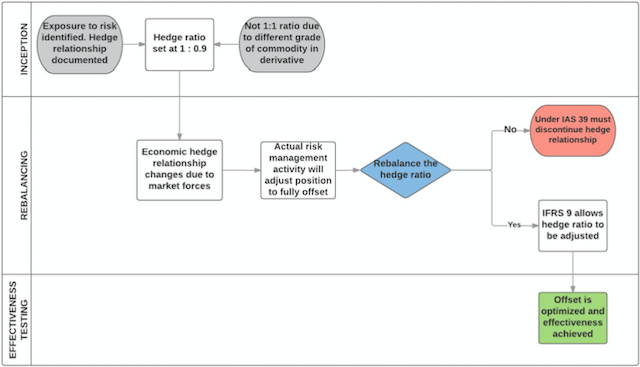

When the economic relationship changes between the hedged item and the hedging instrument due to basis risk, under IFRS 9 you can make adjustments to the hedge ratio on a prospective basis allowing continuation of the hedging relationship.

It is worth emphasizing that basis risk needs to exist between the hedged item and hedging instrument for rebalancing to be relevant.

Rebalancing affects the relative sensitivity between the quantities of hedging instrument and hedged item. Changes to designated quantities of hedged item or of hedged items for a different purpose than adjusting the hedge ratio does not constitute rebalancing.

This is a new concept brought in by the IASB; under IAS 39 if the hedge ratio is altered then the hedging relationship must be discontinued which can result in effectiveness to profit and loss. Therefore, rebalancing is seen as a positive change as it removes the requirement to discontinue and record ineffectiveness.

Refer to my previous article for more detail on the overarching principles of hedge accounting under IFRS 9, but ultimately it is to align the accounting more closely with economic hedging strategies, and this principle is no more evident than in the concept of rebalancing, as explained further below.

How do we do it?

Rebalancing is done by either altering the hedged item or the hedging instrument.

We do this to align accounting with what has happened in the actual basis relationship and also to ensure the effectiveness of the hedge.

An example would be if the hedge ratio used in the actual basis relationship has changed. In practice, risk managers with risk exposures alter and adjust their hedge position when market conditions change.

In some circumstances, the hedge ratio for commercial risk management may be different to the hedge accounting ratio, if, the hedge ratio for risk management would result in ineffectiveness which would then achieve a different accounting result. This would go against the principle of IFRS 9 explained above.

The above example under IAS 39 would require the onerous task of discontinuing that specific hedge relationship and starting a fresh designation relationship.

This would be particularly troublesome in a cash-flow hedge relationship as it would most likely lead to profit and loss volatility. This would be due to the cumulative movements of the derivative having been parked in equity now being transferred to profit and loss with nothing to offset against it, as the highly probable underlying exposure (the hedged item) would not currently be recorded on the balance sheet.

Therefore, IFRS 9 will remove the formal designation and re-designation of hedge relationships in some cases, which has to be seen as a good thing.

It is worth noting that under IFRS 9 the hedge relationship is still required to be discontinued under the following circumstances:

- The risk management objective has changed

- Economic relationship no longer exists

- Credit risk now dominates the relationship

Example 1: ABC Plc

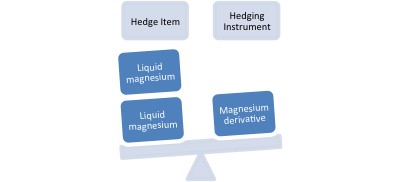

ABC Plc is a manufacturing company with exposure to commodities, primarily input costs of magnesium. To manage this risk of rising magnesium costs they enter into a commodity derivative to hedge the exposure.

There is a strong correlation between the value of the hedged item (the price paid by ABC Plc to their supplier for magnesium) and the magnesium derivative (the hedging instrument), however due to the manufacturing process the magnesium purchased for manufacturing (hedged item) is of a higher value than the derivative, as it is in liquid form, therefore to achieve an optimum offset ABC Plc sets a hedge ratio of 1:0.9 (0.9 hedged item to 1 derivative reflecting the price differential of 10% due to basis risk).

Typically a risk manager will in this instance take out some more cover in the form of an offsetting derivative to true up the position.

Under IFRS 9, ABC Plc can rebalance the hedge ratio to 1:0.8 and designate the offsetting derivative in the hedge relationship, which has an offsetting effect of reducing the ineffectiveness and optimises the offset.

Without rebalancing the extra 10% would be recognised as ineffectiveness volatility in profit and loss as effectiveness would have been tested on the hedge ratio at inception of 1:0.9

IAS 39 does not allow ABC Plc to adjust the quantities that were documented at inception of the hedge relationship and so ABC Ltd would have to discontinue and re-designate a new relationship.

Example 2: Airlines

Kevin has kindly permitted me to add one more example for you, so what follows is actually written by me (Silvia).

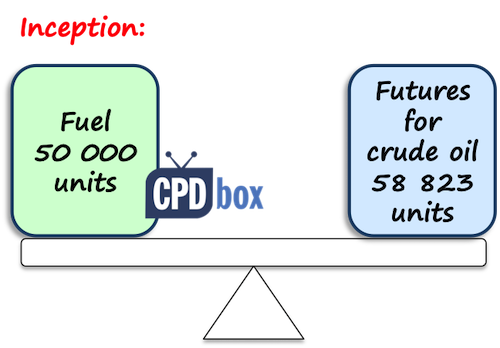

A local airline plans to buy 50 000 units of fuel in 6 months. The airline is worried about constantly rising prices of fuel and therefore, it wants to hedge its exposure.

The perfect match would be to get some derivative related to fuel, however, no such a thing is available on the market and therefore, the airline decides to hedge its exposure by getting commodity derivative – futures for crude oil.

Similarly as in the above example, the airline cannot buy 1 unit of crude oil future to hedge 1 unit of fuel.

Why not?

The reason is that crude oil is just one part of fuel’s total composition.

In reality, hedging managers need to examine what’s the best fit to hedge certain exposure. For example, they would perform a regression analysis to find out the correlation between the prices of crude oil and the prices of fuel.

If there is some correlation, well, then crude oil futures can be used to hedge fuel, but certainly not in 1:1 ratio, as there are two different things and there’s no perfect match.

Let’s say that the airlines hedging experts calculated that crude oil trades approximately at 15% discount compared to the fuel prices (a side note – sorry if that’s not true, I just made these numbers up).

As a result, the hedge ratio is set to 0.85:1 and in other words, to hedge 50 000 units of fuel, the airline buys commodity futures for 58 823 (50 000/0.85) units of crude oil (hint: as futures are standardized contract, buying the exact amount would be probably hard).

At the time of hedge inception, the fuel trades for CU 1.90/unit and the futures for crude oil trade for CU 1.615/unit.

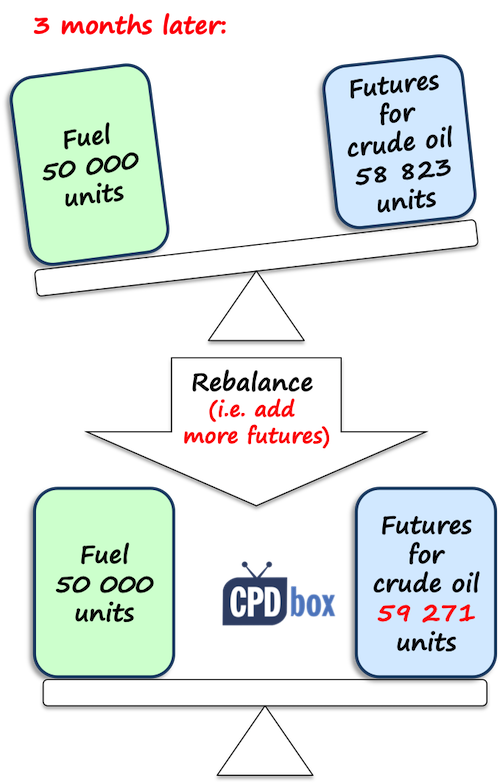

After 3 months, the fuel trades for CU 1.95 per unit and the futures trade for CU 1.645 per unit.

Therefore:

- The change in fair value of hedged item (fuel) is 50 000*(1.95-1.90) = CU 2 500,

- The change in fair value of hedging instrument (futures) is 58 823*(1.645-1.615) = CU 1 765

The hedge effectiveness calculated under IAS 39 is 70.65% (1 765/2 500). This is ineffective as it falls outside “80-125% window”. As it’s actually an under-hedge, the full change in fair value of hedging instrument is recognized in other comprehensive income.

Under IAS 39, the airline would need to discontinue the hedging relationship as this hedge is not effective.

Under IFRS 9, the airline needs to rebalance – or change the hedge ratio.

How?

Certainly, it is necessary to buy more futures to hedge the same amount of fuel. For simplicity, we can calculate it as 50 000*1.95/1.645 = 59 271, based on current prices, but again, new regression analysis would be needed.

And that’s it. The hedge is rebalanced and at the next reporting period-end, the airline needs to assess the hedge in new ration of 50 000:59 271, or 0.84:1.

Hint: do not forget to update your hedge documentation!

About the author

His expertise spans end-to-end accounting functions, including financial control, system analytics, hedge accounting, financial statement preparation and treasury operations. This provides an ideal base and position to understand clients’ needs, in order to deliver best practice advice.

Kevin is a fellow of the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA 2005) and has completed the Certificate in International Treasury Management with the Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT).

Download your FREE Checklist here on IFRS 9 Hedge Accounting which contains some key discussion points around the new standard and the changes from the old standard IAS 39.

Tags In

JOIN OUR FREE NEWSLETTER AND GET

report "Top 7 IFRS Mistakes" + free IFRS mini-course

Please check your inbox to confirm your subscription.

17 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Comments

- Refilwe on Our machines are fully depreciated, but we still use them! What shall we do?

- mekonnen on How to Account for Government Grants (IAS 20)

- Sewa PA System on How to account for intercompany loans under IFRS

- ASHAGRE TILAHUN TAYE on IFRS 17 Example: Initial Measurement of Insurance Contracts

- Silvia on Example: IFRS 10 Disposal of Subsidiary

Categories

- Accounting Policies and Estimates (14)

- Consolidation and Groups (24)

- Current Assets (21)

- Financial Instruments (54)

- Financial Statements (48)

- Foreign Currency (9)

- IFRS Videos (65)

- Insurance (3)

- Most popular (6)

- Non-current Assets (54)

- Other Topics (15)

- Provisions and Other Liabilities (44)

- Revenue Recognition (26)

could you please write the journal entry for the second example (airline) ?

Thank you

In the last example (airlines), can you also change the quantity of the hedged item for rebalancing the relationship? It’s clear that you need to buy an additional contract of oil but, not clear if you can change the hedged item for the rebalancing.

Thanks Silvia for the simplification

Excellent article with great examples. However I didn’t understand, why we take the change in fair value of Hedging instrument to OCI and not in P&l in case where it’s under hedged i. e. Less than 80% under IAS39. I thought all fair value changes on hedging instrument and hedged item will be taken to p&l if hedging effectiveness is not met under IAS39.

Dear Ankit, hm, I see what you mean and I admit it might be confusing.

If there is an underhedge, it is still effective, because the full FV change on hedging instrument offsets some FV change in hedged item, therefore it is recognized in other comprehensive income. The ineffective part arises only when there’s anything left that does not offset the FV change on hedged item – i.e. when there’s an over-hedge.

However, if the underhedge is so low that it falls out of 80-125% window under IAS 39, then the hedge is NOT highly effective and as a result, an entity would discontinue the hedge accounting from that date PROSPECTIVELY, so to the future. I hope it’s clearer now. S.

Hats off to master who is expert presenter of complex topics in most lucid and understandable manner. It is gift combined with hard work perhaps. Keep it up and all the strength for you.

Regards,

Chandra Sekhar

Excellent writing Silvia, very well explained? but one thing in common practice rebalancing is followed? that’s the reason why most companies goes for hedge effectiveness testing. I guess this is not a new concept.

Dear Ghanshyam,

no, rebalancing is not a new concept, companies did it in the past too – but, they needed to stop hedge accounting and start the new “case”. IFRS 9 changed only the fact that when your hedge is ineffective, you can still rebalance and not stop completely+start a new hedge. S.

Thank you Kelvin and Silvia.

Silvia as usual, I am suprised how you can explain such difficult issues in such easy way for understanding. The second part of the article helped me to get what was in the first.

Thank you, Olga, glad to help 🙂 Hedge accounting is a difficult area though and it’s hard to explain it clearly. We tried! 🙂

Very well explained Kevin !

Thank you so much Silvia for this precious article, but can we get more articles for the hedge accounting under the IFRS9, seems that this is a very important subject that we need to be strongest in.

Thank you so much 🙂 good luck

Excellent article!! explained a complex topic in such a simple way. Thanks to Kevin and Sylvia

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed!

Thanking you for great writing!

Thanks to Kevin 🙂