The Quick Guide to IFRS 7 Risk Disclosures

The financial instruments belong to the most complicated and difficult areas in IFRS and therefore, I dedicated many articles to making the things understandable a bit.

However, until now, we haven’t even touched the complexity of the disclosures about financial instruments as required by IFRS 7 Financial Instruments: Disclosures.

Therefore today, I’m happy to publish the guest post written by Mr. John Orford who will guide you through the basics of risk reporting under IFRS 7.

This article reflects the opinions and explanations of John and here’s what he has to say:

More often than not, the fruitful areas of life or one’s career come when we have to fuse two areas of expertise into one.

Be that coding up a Visual Basic script to make your everyday reporting tasks easier; or combining Indian Jalfrezi tomato sauce to your Italian pasta dish (try it – you might be surprised!).

Unfortunately these situations can also be the most worrying for those who are not fully conversant in both fields.

IFRS 7 requires disclosure of quantitative risk analysis which is rarely found outside of front office trading desks.

On the one hand, these are inherently interesting topics, on the other in my experience many accountants don’t know where to start.

Let’s start at the beginning.

Quant by Any Other Name

Be under no illusions, while straightforward and succinct from a risk analyst’s perspective the requirements are both comprehensive and would provide a solid starting point for any company looking to utilise quantitative risk management as part of their internal decision making processes.

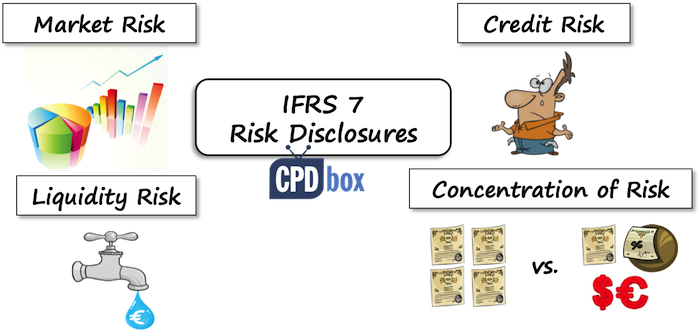

There are four quantitative areas of concern identified by IFRS 7.

- Market Risk. I.e. a comprehensive summary of how future changes in the business environment and markets will impact our assets.

- Liquidity Risk. The other side of the coin of freely fluctuating assets are those that are illiquid. We need to analyse when cashflow payments from these assets are due.

- Credit Risk. Drilling down on illiquid assets – there is a likelihood that we never see the scheduled payments, which we need to quantify.

- Concentration Risk. If diversification is the only free lunch in quantitative finance, concentration is lunch in the most expensive restaurant in town. We have to show whether we are overly exposed to specific companies, geographies, currencies etc.

Risky Business

Before we dive into each requirement in more detail let’s think about what risk analysis actually is.

You cannot touch risk, smell it or see it. It’s invisible and yet very real. People viscerally feel potential danger and try to avoid that feeling if they can.

Financial risk is like any other risk. We can *never* fully measure it directly but many are able to recount times about not being able to sleep due to that feeling of *potential* loss.

Quantitative risk analysis is really just a collection of numerical analogies which are designed to approximate different aspects of that feeling.

When risks are openly accounted for everyone can sleep better at night.

Market Risk Analysis

Firstly we are asked to provide a sensitivity analysis for each market risk factor.

Identifying market risk factors is an art in itself, but usually we derive them from the information needed to value a security.

For example, a bond’s market risk factors are its issuer’s credit quality and the interest rate. Employee stock option’s will be the underlying stock’s price and volatility.

Our sensitivity analysis will shock each of these factors, and we will input these shock values into our quantitative valuation models to derive a loss figure.

This is of course easier said than done, especially when we are valuing complicated products!

Note, that if other summary measures of market risk already used by management, we can use them too, essentially the aim is to get an over-the-shoulder view of corporate risk mitigation.

Liquidity Risk

Many of the greatest minds have philosophised about liquidity, but there is no single agreed upon definition.

Luckily IFRS 7 makes this easy by defining it as a maturity analysis of current financial liabilities.

This can either be a straightforward bucketing by time to maturity or a duration analysis.

Duration is a calculation used to calculate the weighted average time of repayment which is a more accurate measure.

We can calculate duration in a variety of ways, but care should be taken when we are calculating it for complicated securities as there are many pitfalls.

Credit Risk

Ever-topically, analytical credit risk measures are required for assets which have run into trouble or those which we do not have any other means to assess their credit quality.

Luckily this is not difficult, if we already have the quantitative models to calculate market and liquidity risk.

What we are usually looking for is a credit spread for each fixed income asset. We find this by jotting down the current fair value of the asset, and then valuing the asset as if it were valued like a government bond.

The difference is the ‘Credit Value Adjustment’ or CVA. The larger the difference the larger the credit difficulties of course, and with the right quantitative model we can encapsulate this risk in a number called the credit spread.

Concentration Risk

Summarising this information correctly is often an art rather than a science.

Most of the time for example, duration needs to be aggregated as a weighted average of the current net present value of each security, for example. Most of the time.

Once we summarise at the top level we can also look to bucketing our risk by more qualitative means.

Are we exposed to a specific country, industry or currency more than is ideal? Apart from anything else, identifying these concentrations is sound management practice.

Conclusion

I used to call myself an amateur accountant, when I was a hedge fund risk analyst, I had to trawl through hedge fund financial statements to ensure my analytics reconciled against the ‘real’ numbers. I got a real kick out of it.

Hopefully I have given you a taste of risk analysis, and tempted you to take a bite.

Now, I wonder whether I should have grilled cheese on sushi; or ice cream and french fries for dinner…

About the Author

Tags In

JOIN OUR FREE NEWSLETTER AND GET

report "Top 7 IFRS Mistakes" + free IFRS mini-course

Please check your inbox to confirm your subscription.

10 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Comments

- Silvia on How to Account for Decommissioning Provision under IFRS

- Silvia on What is the lease term of cancellable property rental contracts under IFRS 16?

- James Carter on How to Account for Decommissioning Provision under IFRS

- Moses Felix on IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment – summary

- Moses Felix on Summary of IFRS 5 Non-current Assets Held for Sale and Discontinued Operations

Categories

- Accounting Policies and Estimates (14)

- Consolidation and Groups (24)

- Current Assets (21)

- Financial Instruments (54)

- Financial Statements (48)

- Foreign Currency (9)

- IFRS Videos (65)

- Insurance (3)

- Most popular (6)

- Non-current Assets (54)

- Other Topics (15)

- Provisions and Other Liabilities (44)

- Revenue Recognition (26)

Can you please simplify IFRS 7.

i use to glad anytime am reading ur articles on ifrs, please i still wont to know more about the different between our various old standard and ifrs in term of their treatment.

Dear Silvia,

I am very happy about this website. reading your articles helped a lot to clear the doubts.Could you please publish an article on Inventories especially accounting of receipt of Free goods received from supplier and sold to clients at regular sales prices .can we show qty without any values(Zero Value) in Inventory as per IFRS

Explanation was confined to theory. I wish you could have given few illustrations of how risk factors are disclosed.

Madam

I have a small doubt In India MNC Companies preparing Consolidated Financial Statements under IGAAP and IFRS. depreciation disclosed in as per IGAAP in Financial Statements. But not Disclosed as per IFRS Consolidated Financial statements. Is there any Provision for that?

Hi Madam

i read this article on IFRS 7 it is very useful to my research .

And today burning issue in global accounting standards. i have a small doubt how can we Apple cable TO BANKING ORG ?

Mam i told you i will send my article on IFRS for publish in your country JOURNAL but still it is not completed.

Good night Madam.

thank you.

Satyanarayana garudasu

Research Scholar,

Osmania University

Hyderabad.

hi silvia i want to find out. i read an article where they said trade recevables are an example of a financial instrument.whats your comment?

regards.

True! 🙂

I Really love you Cute smarteeee…

you Really worked On IFRS’S….

A good Topic and a good explanation.I wish you can do the same on IFRS 9